Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) announced on February 6th that it will reopen the Nostrand Avenue station entrances to the A/C lines, that have been closed for the past 30 years, to accommodate the overcrowded rush-hour. The Nostrand Avenue station currently has only one entrance each for both Manhattan-bound and Rockaway-bound. Construction will begin as part of the MTA’s 2020–2024 Capital Plan. Though the planned completion date is unknown, it will definitely ease one of the problems that has been caused by gentrification in the area.

I was actually one of the people who believed in this plan, and suggested that the Nostrand’s closed subway entrances be reopened. It’s an obvious solution that needed to be implemented. However, at the time of my research in 2016, the MTA did not have the funding to get it done.

In the Policy Analysis class I took during graduate school back in 2016, Professor Karl Kronebusch, who was connected to the city and state officials, assigned students to select one issue that surrounded them, as well as three feasible policy alternative recommendations for the issue. Then, in the conclusion of the final paper, each student had to narrow down the recommendations to one. The professor said that he would submit some of our recommendations to the city and state officials.

The issue I selected was “gentrification.” The three recommendations I came up with were “rent stabilized protection for long-term residents facing eviction,” “collecting taxes from developers to fund MTA to improve the nearby subway system,” and “restrictions on new retail businesses in the area.” Out of all three, I concluded that “collecting taxes from developers to fund MTA to improve the nearby subway system” to be the most conceivable solution to Franklin Avenue gentrification. And plan included the reopening of closed Nostrand Avenue entrances.

Please read my term paper, that I’d written in 2016, which I have copied and pasted below from my original Word file. In four years, the situation in my neighborhood has changed in many ways. I’d like to share this paper not only for people to have a better understanding of my neighborhood, but also to remind myself the history of my hood.

Nana N Yoshida

July 18, 2016

Baruch College (City University of New York)

.

Policy Alternatives for Gentrification Issues in the Franklin Avenue Area

.

Executive Summary

Gentrification has probably been one of the biggest issues for many residents in Brooklyn, NY, for the past few years. In this paper, the policy alternatives that will improve the quality of life for both new and long-term residents will be discussed. In order to do so, first, the issues of gentrification in Brooklyn will be analyzed. Among all areas in Brooklyn, this paper will focus particularly on the border between Crown Heights and Prospect Heights, especially Franklin Avenue between Fulton Street where the C trains stop and Eastern Parkway where the 2,3,4, and 5 trains stop (From here on referred to as “the Franklin Avenue area”).

The changes in the neighborhood did not occur slowly—it suddenly started around 2006. Ever since then, the neighborhood has changed dramatically. It all started with few fancy restaurants, cafes, and bars that opened in vacant retail spaces. As the demand for the retail spaces in the area grew, old businesses closed their doors due to increased rent. Local mom-and-pop stores that did not survive were replaced by a cafe, restaurant, or bar opened by newcomers. Corner stores that have survived through gentrification took advantage of the change and have renovated their stores to attract the new types of customers. The Franklin Avenue area suddenly became a hip, trendy area where people from Manhattan came to visit.

While some business owners and landlords in the area are happy making a larger profit, many residents, both old and new, have some complaints on the issues caused by gentrification. For example, some long-term residents unfortunately had to move out of the area after enduring rapid rent increases for several years. Some of the other long-term residents who have remained in the neighborhood, either because they own their home or live in a rent stabilized apartment, prefer the neighborhood the way it used to be. Gentrification is often blamed for increased cost of living. Gentrification has also created chaos in the formerly “quiet” neighborhood with noisy bars and restaurants. It is the reason why the subway has become overcrowded. New residents complain about the subway system while they are the ones who have contributed in causing the overcrowdedness.

Stone (1997) mentioned that the members of a community almost always have an interest in its survival, and therefore in its perpetuation and its defense against outsiders.[1] The “us against them” mentality not only causes separatism and produces anger against others, but it could also lead to a crime. The area of Nostrand and Franklin Avenues are especially crime riddled and have perplexed the 77th Precinct’s command for years.[2] The 77th Precinct, which covers the Franklin Avenue area, saw 17.2% increase in major crimes since gentrification from 2010 to 2011 alone.[3] The ultimate goal here is to find the best policy alternative that will make both new and long-term residents satisfied with what the new Franklin Avenue area has become.

Recommendation 1: Rent stabilized apartments reserved for long-term residents facing evictions

The first alternative is to provide long-term residents some kind of protection that will reduce the risk of displacement. One way to do this is to make changes to the current rent stabilized apartment policy in favor of long-term residents. Whenever there are vacancies in rent stabilized apartments, those apartments should be reserved for old residents who are facing eviction from their unregulated or deregulated apartments. Currently, anyone who lives in a rent stabilized apartment is protected from excessively high rent increases. Also, if the tenant or the spouse of the tenant is a senior citizen or is disabled, unless the landlord provides an equivalent or superior apartment at the same or lower rent in a nearby area, landlord is not allowed to evict a tenant from the rent stabilized apartment.[4] Anyone is eligible to apply to live in a rent stabilized apartment. However, there aren’t enough rent stabilized apartments for all residents. The way their application is reviewed by landlords is no different from that of market-rate apartments. There is an equity issue in the rent stabilized apartment regulation.

In order to help residents facing displacement in the Franklin Avenue area or other areas in New York City, first, the rent stabilized apartment program should be eligible to New Yorkers only. Second, whenever there are vacancies for rent stabilized apartments, the long-term residents who are facing eviction from their unregulated or deregulated apartments should have priority to move into that apartment. The qualified long-term residents to be prioritized should have lived in New York City for the past ten years. Providing incentives such as tax benefits to landlords who house those prioritized residents might encourage landlords to participate in this practice.

Recommendation 2: Imposing “Commuter congestion tax” on real estate developers to fund MTA to improve subway system

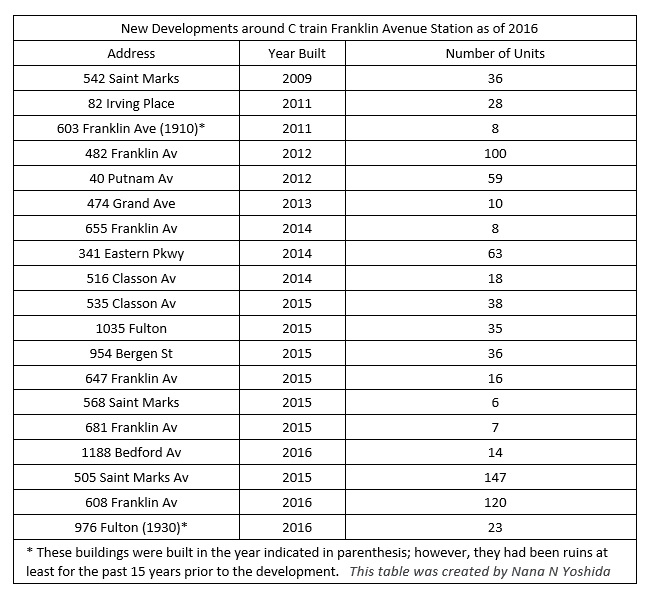

The second alternative to solve the gentrification issues is to eliminate the overcrowded morning commute in the Franklin Avenue area. There has been a large increase in the number of residents who commute to Manhattan from C train Franklin Avenue station. The C train has been overcrowded since the start of gentrification. This problem has worsened every year and something should be done to help ease the morning commute for the residents. Adding to the current situation, the number of people who commute from that station is expected to climb even more. There are a couple of new apartment complexes in the Franklin Avenue area that have just been constructed (Table 1).

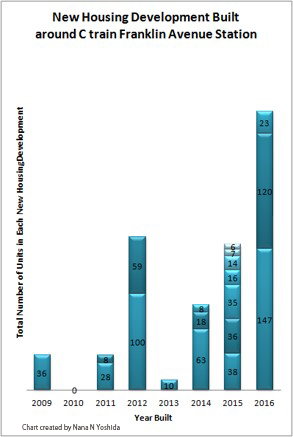

505 Saint Marks Avenue has just opened a brand new apartment complex with 147 units in 2016.[5] 608 Franklin Avenue is currently constructing an apartment complex with 120 units that is planned to be on the market sometime this year in 2016.[6] Key Foods and other stores at a two-story building at 1134 Franklin Avenue, which is right on the corner of Fulton Street where the C train station entrances are located, has been vacated since 2015 and is going to construct a new 119-unit housing complex above brand new stores. The construction for this building has not yet started; therefore, I did not include this building in my analysis.[7] Chart 2 shows the new housing development, each with its number of units, built around the C train Franklin Avenue station since 2009 based on Table 1. Chart 3 shows the cumulative numbers of new housing development units since 2009, based on my research shown in Chart 2.

The methodology used here for creating these charts was as follows: coming across new buildings by walking in the Franklin Avenue area; and rearching the buildings’ address online to find out the construction year and the number of units. Since these research results only include buildings that caught my eye, the actual number of all newly constructed buildings will be more.

The C trains are so overcrowded, during morning rush hour, many train riders at Franklin Avenue station must wait for several trains before they can even get on the train. Even during rush hour, the local C trains only run 7 cars per hour while the express A trains run 18 cars per hour.[8] However, increasing the number of trains may increase train congestion, which might result in added train delays. So instead of changing the frequency, the capacity of the trains should be addressed.

The main factor is that the local C trains are shorter than the express A trains. C trains are 480-foot long while A trains are 600-foot long while all C train stations’ platforms are the same length as A train station platforms. Perhaps, C trains should also have 600-foot trains at least during morning rush hours. MTA states in a report that the 480-foot C trains are causing problems of uneven loading and overcrowding in the first and last cars. It also states that this problem can be prevented by implementing a low-cost alternative to have C trains to stop at the position where car doors are close to the stairs.[9] However, that will only help the situation during off-peak hours because during rush hour, all the train cars, not just the first and last cars, are full. According to MTA, extending C trains to 600-feet long would require additional 44 cars at a cost of over $100 million and it is not included in the current MTA Capital Program.

At the same time, MTA did a case study on reopening a set of closed Nostrand Avenue station entrances. Nostrand Avenue station, which is located right next to Franklin Avenue station, is accessible to both express A and local C trains. The closed Nostrand Avenue station entrances are located on Bedford Avenue, which is right in between Franklin Avenue and Nostrand Avenue. Reopening this station should increase the number of commuters who take the A train instead of the C train. Since Nostrand Avenue station’s existing entrances are not wheelchair accessible, reopening of closed Nostrand entrances will require American Disability Act (ADA) compliant elevators or ramps. Though the cost of reopening the ADA compliant entrances is not known, the cost of reopening a non-ADA compliant entrances is over $32 million. The MTA report states that this alternative is being considered as long as MTA gets funding for it.[10] Without getting funded, this alternative, as well as the other alternative to have C trains longer, will not happen.

To expedite the implementation of these alternatives, it should be fair to impose “taxes” on the developers of new housing complexes. (I will call this new tax “commuter congestion tax” from here on in this paper.) The funds collected as the commuter congestion tax will be used to improve the local MTA train stations. However, levying this kind of tax on small homeowners and small apartments may not be fair. The developers who should be subject to commuter congestion tax are the ones who are planning to build a housing complex with 50 units or more. Ironically, developers of multiple dwellings, who filed for 421-a permit before it expired in January 2016, are exempt from tax for at least 10 years for a new housing complex built in a vacant lot.[11] Though the Franklin Avenue area was covered within Geographic Exclusion Area for this tax incentive program, as long as the new complex included 20% affordable units with 80% market-rate units, developers were eligible for the 421-a program.[12]

The 421-a incentive program was enacted in 1971 as a way to combat declining property values and a downturn in the city’s population.[13] Obviously, this problem no longer exists. 421-a expired in January 2016 because real estate developers and construction labor unions could not reach an agreement on how to reform the law before its deadline. Though the reason for its termination had nothing to do with its original mission becoming obsolete, the expiration of 421-a should contribute as a step toward improving the quality of life for the Franklin Avenue area. Not only should the developers of new housings be ineligible for tax incentives, but they should also be obligated to pay the New York City “commuter congestion tax” that will be paid toward MTA Capital Funding for the improvement of the local train stations. The disadvantage of this alternative is that developers will most likely be opposed to the policy. However, through this policy, developers can contribute to creating positive externalities in the neighborhood. It will help the old and the new appreciate each other.

Recommendation 3: Reserving former houses-of-worship lots for non-profit organizations with good intention

Boosting community togetherness is often overlooked, yet imperative in the gentrified neighborhood. In order to accomplish this, there should be more non-profit organizations that provide common pool resources welcoming both old and new residents, such as art galleries, youth centers, after-school program centers, and elderly recreational centers. Sadly, whenever a ground floor retail space is on the market, it is usually taken by business owners who are willing to pay the highest rent. In order to have spaces with positive motives in the neighborhood, there must be a policy alternative to make this happen smoothly.

The best places for this would be former houses of worship. Brooklyn was home to dozens of synagogues, churches, and chapels for many years.[14] Many of the large churches and synagogues were replaced by condominiums, and small scale houses of worship in the middle of blocks have been replaced by for-profit businesses.[15] In this way, not only the lots of former for-profit businesses, but also the lots of former houses of worship were replaced by cafes, restaurants, and bars targeting the new residents in the neighborhood. Some long-term residents do not feel welcomed in the new businesses, especially when the business is charging a lot for just a cup of coffee.

To preserve the good old neighborhood, all lots of the former houses of worship should only be allowed to be replaced by non-profit organizations or institutions that provide common pool resources to both long-term and new residents.

To implement this policy, first, there must be a new zoning resolution that regulates the number of for-profit businesses in the Franklin Avenue area. Currently, there are no resolution that regulates this.[16] To really improve the community togetherness, there should be government grants for qualified non-profit organization with a mission dedicated to help the people of the Franklin Avenue area to understand each other. Having such organizations in the Franklin Avenue area will have a positive neighboring effect.

Conclusion

I recommend all above policies alternatives to be implemented to improve the quality of life for everyone facing gentrification issues in the Franklin Avenue area.

The first alternative–to reserve vacant rent stabilized apartments for the long-term residents facing eviction–should work best in the beginning of gentrification. However, the Franklin Avenue area actually has already passed that stage of gentrification. Most long-term residents who faced eviction have already moved out of the area without getting sufficient protection. While I would definitely recommend this alternative to the districts where gentrification is expected to happen in the near future, it may no longer be the priority in the Franklin Avenue area.

In the Franklin Avenue area particularly, I would recommend the second policy alternative–to impose taxes on developers of new housing complexes to fund the MTA to improve the morning commute experience for both new and long-term residents. This should solve the most concurrent crucial issue the Franklin Avenue area is facing today.

The third alternative–to restrict the for-profit businesses to open in former lots of houses of worship–may face difficulty accomplishing the goal of community togetherness. It may also be difficult to measure the end results since the level of change in each individual’s understanding on the subconscious level is extremely difficult to measure. However, implementing this alternative too will be a step toward making the quality of life better for all residents in the Franklin Avenue area.

So to start, let’s focus on solving the issue of overcrowded commute for the residents of Franklin Avenue area by improving the MTA subway system.

[1] Stone, Deborah. (1997). Policy Paradox. 21.

[2] City of New York. Department of City Planning. (Fiscal Year 2009). Community District Needs for the Borough of Brooklyn. 176.

[3] Gendar, Alison. (2011). Brooklyn’s 77th Precinct probed for manipulating crime statistics. New York Daily News.

[4] Schneiderman, Eric T. (n.d.) Tenants’ Rights Guide. 17. Retrieved from https://www.ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/Tenants_Rights.pdf

[5] 505 Saint Marks Apartment Complex’s website http://www.505saintmarks.com/

[6] Sherman, John. (2014, October 22). Don’t Feel Bad for Wealthy Newcomers on Franklin Avenue. Brooklyn Magazine on the Web.

[7] Mashayekhi, Rey. (2015, May 12). Joseph Brunner to bring 119-unit rental building to Bed-Stuy. The Real Deal New York Real Estate News on the Web.

[8] New York City Transit. (2015, December 11). Review of the A and C Lines. 14. Retrieved from http://web.mta.info/nyct/service/pdf/AC_LineReview.pdf

[9] New York City Transit. (2015, December 11). Review of the A and C Lines. 30. Retrieved from http://web.mta.info/nyct/service/pdf/AC_LineReview.pdf

[10] New York City Transit. (2015, December 11). Review of the A and C Lines. 73. Retrieved from http://web.mta.info/nyct/service/pdf/AC_LineReview.pdf

[11] New York City. Dept. of Housing Preservation and Development. Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/developers/tax-incentives-421a.page

[12] Baird-Remba, Rebecca. (2015, July 17). Tracking Large Developments and Affordable Housing in Crown Heights. New York Yimby on the Web.

[13] The Municipal Art Society of New York. Retrieved from http://www.mas.org/urbanplanning/421a/history/

[14] Osman, Suleiman. (2011). The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn. 46. New York: Oxford University Press.

[15] Upadhye, Janet. (2014, June 17). Brooklyn’s Historic Churches Disappear to Make Way for Condos. DNA Info on the Web. Retrieved from

[16] New York City. Dept. of City Planning. The Zoning Resolution. Retrieved from http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/zoning/districts-tools/residence-districts-r1-r10.page